The Future of Mental Health: Rethinking How We Support Wellbeing

Samuel Brooks on 19th Dec 2025The way we understand mental health is changing faster than the systems designed to support it. While research, technology, and public awareness continue to advance, many still encounter fragmented care, limited access, and approaches that prioritise symptoms over context. So how might it look going forward and what should we hope for in order to get there?

It’s a big topic so this submission in no way attempts to be comprehensive. And of course, the landscape changes as our understanding does.

What is mental health?

Mental health is a term floated around so much that it's important to distinguish what is meant. In recent times it has shifted from meaning simply an "absence of illness" to a broader sense of psychological wellbeing. The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines mental health as:

Mental health is a state of mental well-being that enables people to cope with the stresses of life, realize their abilities, learn well and work well, and contribute to their community [1].

Of course, there are distinctions between mood and longer lasting feelings. Mental health is often used interchangeably between these but for the benefit of this article I am meaning cycles of thought or feelings attributed to well-being.

Historical views on mental illness

Although we have made significant progress regarding the stigmas of mental health, there is an historical context that has undoubtedly influenced how we perceive it. It’s a broader discussion that includes more social-psychological topics such as how we determine the sane, which as the validation of others’ perceptions of reality. Countless authors and scholars down the years have explored the subject, from Michel Foucault (1926-1984) to Ken Kesey (1935-2001). And there have been many examples of how mental illness has been interpretated, e.g. being possessed, witchcraft, etc. to explain the causes of its symptoms. As those forementioned intellectuals have theorised, and I think most would agree - these have widely been used as a tool of control ensuring that people are suitably incentivised to conform.

Before the 19th Century, those deemed mentally ill were sent to workhouses or prisons. With pressure from various social campaigners, the Victorians were the first to assign legal responsibility for them to local authorities and asylums were made mandatory. The focus shifted from custody to cure, and the condition was rebranded as treatable [3].

This appears to be an important milestone in addressing the marginalisation of those individuals whilst subsequently recognising that mental health was an issue for us all. Fast-forward to today, where people seem more aware than ever of their mental status, and in contrast to previous generations, are even comfortable enough to openly share the status of their psychological well-being, often on a daily or more frequent basis. It’s a radical change that displays a significant willingness to challenge the stigmas attributed to mental health.

How different societies interpret mental wellness

The National Institute of Mental Health suggests:

.. patients in different cultures tend to selectively express or present symptoms in culturally acceptable ways [4].

Despite varying levels of stigma, in comparison to most cultures, the west tends to be the most open to acknowledgement and treatment (all be it narrowly applied). But NIMH’s research also indicates that there are noticeable differences in how willing and active various ethnic groups (sub-cultures) are in pursuing help, seemingly corroborating their cultural findings.

Indigenous communities tend to associate wellbeing neither exclusively to the mind or body, often attributing manifestations to imbalances or drawing a spiritual significance that is representative of a deficiency.

According to Yellowhead Institute, Indigenous peoples in Canada have a suicide rate of three times the national average [5] But this may reflect less on how they interpret mental health and more on the traumas of marginalisation resulting from colonialism.

There are of course tribes that have a more holistic approach to mental health, focussing on the connectivity of mind and body, a mindset that particular the West, has shown signs of moving towards.

What causes mental health issues?

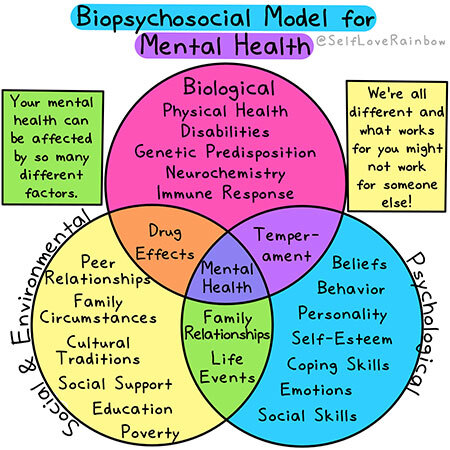

This is akin to asking 'what causes the body to falter?', i.e. it very much depends. People can suffer trauma, bereavement or feel isolated socially. Most mental health issues are multifactorial, not the result of one single cause. As a guide, let’s consider the Biopsychosocial Model for Mental Health

Biological

There may be genetic predispositions, physical health conditions or events, such as brain damage, that can affect the tendencies of individuals. Most are to be managed rather than cured.

Psychological

Including personality traits, emotions, belief systems and coping mechanisms. The way in which an individual responds to stress or interprets life events can significantly influence their mental well-being.

Social

This refers to relationships, social support networks, cultural background, socioeconomic status, and life experiences. Social isolation or exposure to trauma can significantly impact mental health.

Evolutionary and Modern Societal Incompatibilities

With the rise in reported mental health issues in the modern era, I think that it’s at least worth considering that many of the root causes could be systemic (aside from the fact that reporting is less actively discouraged). That they (contributing causes) may be instigated by the incompatibility of what the mind determines as attainable versus what is periodically attained. For example, various sources suggest that with the formation of the Printing Press, people were exposed to a wider range of realities that reshaped their localised expectations by processing information that wasn’t applicable on an individual basis [7]. This would indicate that the overall status of the mind is affected by its assessment of how well it believes that it is fulfilling its potential, according to the information at its disposal.

Assuming this to be true then similarly, since the Internet has further connected the world, this has become a factor for us all, effectively making us aware of problems that we, at least on an individual basis, cannot fix, and at a far greater scale.

While these are issues that concern the broader exposure to information, there appears to be deep, underlying conflicts to what we witness online as opposed to those fundamental to societal belief systems. For instance, we are told that we are free, autonomous agents that live in an egalitarian society and yet what many of us see when we broaden our periphery is disparity, disproportion, inequality and injustice seemingly creating a chasm between what we expect and what we actually get.

Closing this gap could be crucial to maintaining a healthy mental status [8]. Of course, it’s not the Internet’s fault per se but rather a commentary upon the infrastructures that we live within, and importantly on the increasingly concentrated cycles of incited consumerism that are dependent on a constant state of crisis.

There is a final observation on the factors of modern living incongruous to our genetic leanings. For those familiar with the concept of a shared reality, meaning anything that we generally agree upon. These are important to create physical, cultural and moral infrastructures by which we interact, a basis upon which we can coexist. Some have proposed that we are gradually losing our ability to contribute to our own shared reality, becoming reality consumers [7].

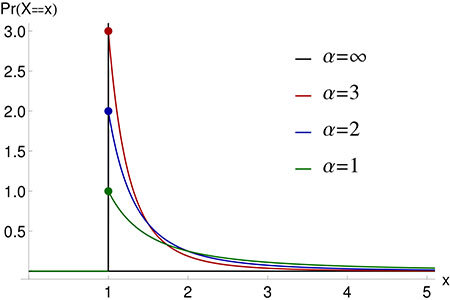

And frankly, this seems hard to deny when you consider how varied access to different opinions is. This is regularly demonstrated in feedback loop patterns administered to search engines and applications, i.e. the more popular something is, the more popular it becomes, corresponding to the Pareto Distribution

Treatments and Approaches

The treatments and approaches toward mental health are vast and varied, relatable to how the mind is culturally and periodically perceived.

Disparity between how we define mental health and how support is delivered

Naturally how we think of mental health is critical as to how we afford support. As covered, previous societies have viewed manifesting symptoms as incurable – madness was deemed an irreversible state and subjects were often incarcerated. Today, at least in the west, mental health is recognised as deeply contextual and personal effected by a multitude of factors (see What causes mental health issues?). So, is care delivered appropriately for this current understanding?

Anyone that’s ever used any health service will know that care delivery relies heavily on standardised treatment pathways that leave little room for individual nuance. In fact, any institution faces the same challenge - customisation being the enemy of scale.

We’re all too aware of the very real resource shortages that would otherwise enable a less hurried, more personalised provision. It’s hard to deny that long waiting times and restrictive eligibility criteria disproportionately affect those with fewer resources, reinforcing inequality through delayed or inaccessible care.

And insurance-based or means-tested systems can discourage treatment or early intervention, making mental health support conditional on financial capacity rather than need.

Yet curiously while mental wellbeing is understood to be intertwined with housing, employment, relationships, and purpose, support is typically siloed within clinical or medical settings, somewhat akin to taking an aspirin to cure a snake bite. With GPs and doctors ordained with the power to determine what is mentally healthy and what constitutes good living. Healthy body we know to be helpful but may not comprehensively equal healthy mind.

Traditional Healing

Traditional healing systems view mental health as a balance between mind, body, community, and environment, rather than an isolated clinical condition and are mostly concerned with natural cures. Methods include herbal medicine, Traditional Chinese Medicine (acupuncture, Tai Chi, etc), Reiki, shamanism and indigenous traditions. Some of which have been practised for centuries by mainly Eastern cultures whose religions and routines have been accommodating to their presence.

Arguably the west’s relatively recent imperialism has caused it to denounce previous approaches. Yet despite the wide-spread evangelising of Christian beliefs (demonising these customs) with a monogamous oath to biomedicine, they continue to be practised, all be it often covertly [10]. Attempts to measure the effectiveness of various treatments are marred with complexity due to the fact that societies that offer alternative remedies are usually within vastly different cultural settings which are continually influencing mental status.

A noticeable difference between traditional and medical approaches appears to be that medicine proclaims to be the only true, definitive purveyor of good health with all else deemed a pseudo-science. The medical community have undoubtedly encouraged society to look down disparagingly and condescendingly on traditional methods as the folly of fools. Well-being has certainly been less prioritised, with more immediate urgency placed on confronting economic hardship or political conflict.

Psychedelics and New Therapies

Having previously been considered part of a pre-enlightened era full of superstition and ritualistic tradition, psychedelics have re-emerged as a potential treatment for addressing imbalances in mental health. The recent attention it has gained has been primarily driven by renewed clinical research rather than countercultural narratives.

Early studies suggest psychedelic-assisted therapies may help address treatment-resistant depression, PTSD, anxiety, and addiction, particularly where conventional approaches have plateaued. These treatments challenge symptom-management models by focusing on meaning, perspective shift, and emotional processing, rather than ongoing pharmacological maintenance.

Perhaps most notorious is psilocybin – the psychoactive compound found in magic mushrooms. My own experiences with psilocybin (in Vancouver, Canada) have helped me to find the loopholes in a deep-rooted, spiralling sadness granting me an ability to cherish the present and reimagine the future - the effects of which have been profound and long-lasting. And I’m not alone - there are countless examples of how it has helped all types of people to better live with traumas or debilitating conditions that threaten their existence [11].

Other contemporary treatments include hypnosis and music/sound therapy, both of which are currently less documented but like psychedelics tend to appeal according to demographics and lifestyle.

Digital and AI-based therapies are increasingly being used (as they are across all spaces), allowing people better access to help. AI is particularly useful in providing personalised treatment pathways, being able to adapt therapeutic content in real time. But it’s undoubtedly a less personable experience which may not be as beneficial to individuals as there lacks the empathy often needed to feel understood.

The shift toward evidence-based approaches

Trends in mental health care show it to be increasingly guided by empirical research and measurable outcomes, moving away from tradition, intuition, or legacy practices alone. There is a growing emphasis on clinical trials, longitudinal studies, and real-world data to validate both new and existing interventions. This being aided by continuing advances in data collection - including digital monitoring and patient-reported outcomes.

Preventative Practices

Aside from trauma-based mental health issues (PTSD, etc), lately there has at least become the awareness that mental health, like the body, is something to regularly monitor and maintain. More commonly thought of as being influenced by our roles that we participate in and are subjected to within the cycle of our daily lives. This helping to form a proactive rather than reactive approach which actively recognises the effects of our routines.

The role of nutrition, sleep, and exercise (biological balance)

It’s likely that we all know someone who occasionally gets “hangry” (angry because they are hungry). Eating and getting suitable nutrition is after all pivotal to (biological) survival so despite it being more evident in some than others - it makes perfect sense that it should affect mood. Over longer periods it would follow that that this would destabilise a person’s perception of themselves and others as well as inhibiting them from performing various necessary functions during the course of their lives.

Even before there was evidence demonstrating exercise to be conducive to mental well-being, doctors were prescribing physical activity as a remedy. Exercise has since been shown to increase serotonin levels, which help to lift mood and combat feelings of depression and anxiety.

Sleep is recognised as a core pillar of mental wellbeing, influencing memory processing, stress response, and emotional resilience. By all accounts, the benefits of good sleep are vast and largely irreplaceable. Chronic sleep disruption is now seen as both a cause and consequence of mental health issues, and with almost 1 in 5 people in the UK not getting enough sleep [12], it’s a factor that is frequently not afforded the attention it warrants.

It’s clearly not as straight-forward as to cite any one biological deficit for an individual’s poor mental health as they demonstrate an impact on each other as other factors influence them, e.g. exercise may improve sleep, sleep may be impeded by anxiety, etc. However, their fundamental role in administering core essentials is beyond doubt.

Community care, mindfulness, and workplace wellbeing (social balance)

Mental health is increasingly shaped by social balance - the quality of our relationships, sense of belonging, and daily social environments. Community-based care models emphasise connection, peer support, and shared experience, helping to reduce isolation that traditional clinical approaches have often overlooked.

In workplace settings, mental health is shifting from reactive support to preventative wellbeing, addressing workload, autonomy, and psychological safety. However, although progress has been made, there are often conflicts with productivity that mean much is reduced to inflated rhetoric that is not satisfactorily applied in practice.

Nature, gardening, meditation, etc. (psychological balance)

Psychological balance is increasingly linked to regular engagement with restorative environments and reflective practices, rather than constant cognitive stimulation. The coronavirus lockdowns highlighted the importance of nature and open spaces upon wellbeing.

During that time, despite the restrictions people were encouraged to take at least one daily walk to alleviate the cabin fever that they were inevitably feeling.

Almost a quarter of Britons (24%) describe themselves as gardeners [13], and as one myself I would (naturally) advocate it as a vocation. Connecting directly with nature, observing & promoting symbiotic relationships, stimulating primal senses, engaging with the eco-systems that we’re part of and arguably more importantly than all - providing an alternative to our confined, immobile, modern routines.

Meditation and contemplative practices support emotional regulation, self-awareness, and resilience, particularly in the face of chronic stress. Recently, they appear to be more widely received as adaptable and less formal with fewer religious or ceremonial connotations, often serving as a welcome opportunity to disengage from the torrent of voices clambering for our attention.

What to expect

As always, much is dependent on the political climate. Assuming that nations and governing bodies are able to avoid volatility, there are many exciting areas to explore and develop that can play a part in progressing our understanding of mental health and how to better optimise it. But I believe that it’s vital to view it as something that isn’t resolved but, like us, is continually evolving in accordance with our natural and cultural settings.

Why now is a turning point

Recent technological advancements such as AI and more robust data collection have given us both more information to make informed decisions and new tools to administer care. Data derived from these developments, has alerted us to the vast scale of mental health issues encountered by a significant number requiring urgent consideration and action. According to Mind [14]:

Truly alarming numbers which are likely to be much higher considering that they don’t include those in hospital, prison, sheltered housing and homeless or rough sleeping.

The call for a compassionate, forward-thinking approach

Forward-thinking approaches recognise distress as a human response to complex conditions, rather than a flaw to be corrected in isolation. But sadly, these perceptions seem in direct conflict with an inflexible model that appears unable to adapt according to the needs of people, instead forcing them to fit to its predetermined ideals.

Any meaningful progress will depend on basing systems around people, considering how to placate individual needs with collective alliance. It seems abundantly apparent that the future of mental health care depends not only on clinical innovation, but on addressing systemic inequality as a core determinant of wellbeing. Support must evolve to reflect the social, biological, and psychological forces that shape mental welfare.

References

1: World Health Organisation - Mental health. Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/mental-health (Accessed 17 December 2025).

2: Kesey, K (1962) One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest.

3: Science Museum (2018) A Victorian Mental Asylum. Available at: https://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/medicine/victorian-mental-asylum (Accessed 11 November 2025).

4: National Library of Medicine (2001) Chapter 2 Culture Counts: The Influence of Culture and Society on Mental Health. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44249/ (Accessed 12 December 2025).

5: McGuire M, Gudgihljiwah J (2022) Let’s Talk about Indigenous Mental Health: Trauma, Suicide & Settler Colonialism. Available at: https://yellowheadinstitute.org/2022/lets-talk-about-indigenous-mental-health-trauma-suicide-settler-colonialism/ (Accessed 11 November 2025).

6: Self Love Rainbow (2021) The Biopsychosocial Model for Mental Health. Available at: https://www.selfloverainbow.com/the-biopsychosocial-model-for-mental-health/ (Accessed 11 November 2025).

7: Redbeard (2022) The Shared Reality Paradigm. Available at: https://red-beard.medium.com/the-shared-reality-paradigm-d52db8eea3ea (Accessed 11 November 2025).

8: Equality Trust (2024) Mental Health. Available at: https://equalitytrust.org.uk/mental-health/ (Accessed 18 December 2025).

9: Noah E (2022) Lesson Four: Healing Circles. Available at: https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/indigenoushealth/chapter/lesson-five-healing-circles/ (Accessed 18 December 2025).

10: Jakarasi M (2024) The Persistence of Traditional Healing for Mental Illness Among the Korekore People in Rushinga District, Zimbabwe. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01459740.2024.2406786#abstract (Accessed 17 December 2025).

11: Morton B (2023) Psilocybin: Calls to ease restrictions on magic mushroom drug. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-65638220 (Accessed 17 December 2025).

12: Mental Health UK (2024) Sleep and mental health. Available at: https://mentalhealth-uk.org/help-and-information/sleep/ (Accessed 18 December 2025).

13: Drake O (2025) First AI mapping of UK’s gardens reveals disparity in access and need for better provision. Available at: https://www.rhs.org.uk/science/articles/uk-state-of-gardening-2025-report-released (Accessed 18 December 2025).

14: Mind (2025) Mental health facts and statistics. Available at: https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-health-problems/mental-health-facts-and-statistics/ (Accessed 18 December 2025).